Cyber Robot AI Wartime

by Christian Wolff

The year is 2056. AI-powered robotic legions hurtle across a vast battlefield in a clash of startling proportion and lasting international consequences. The new face of war has arrived.

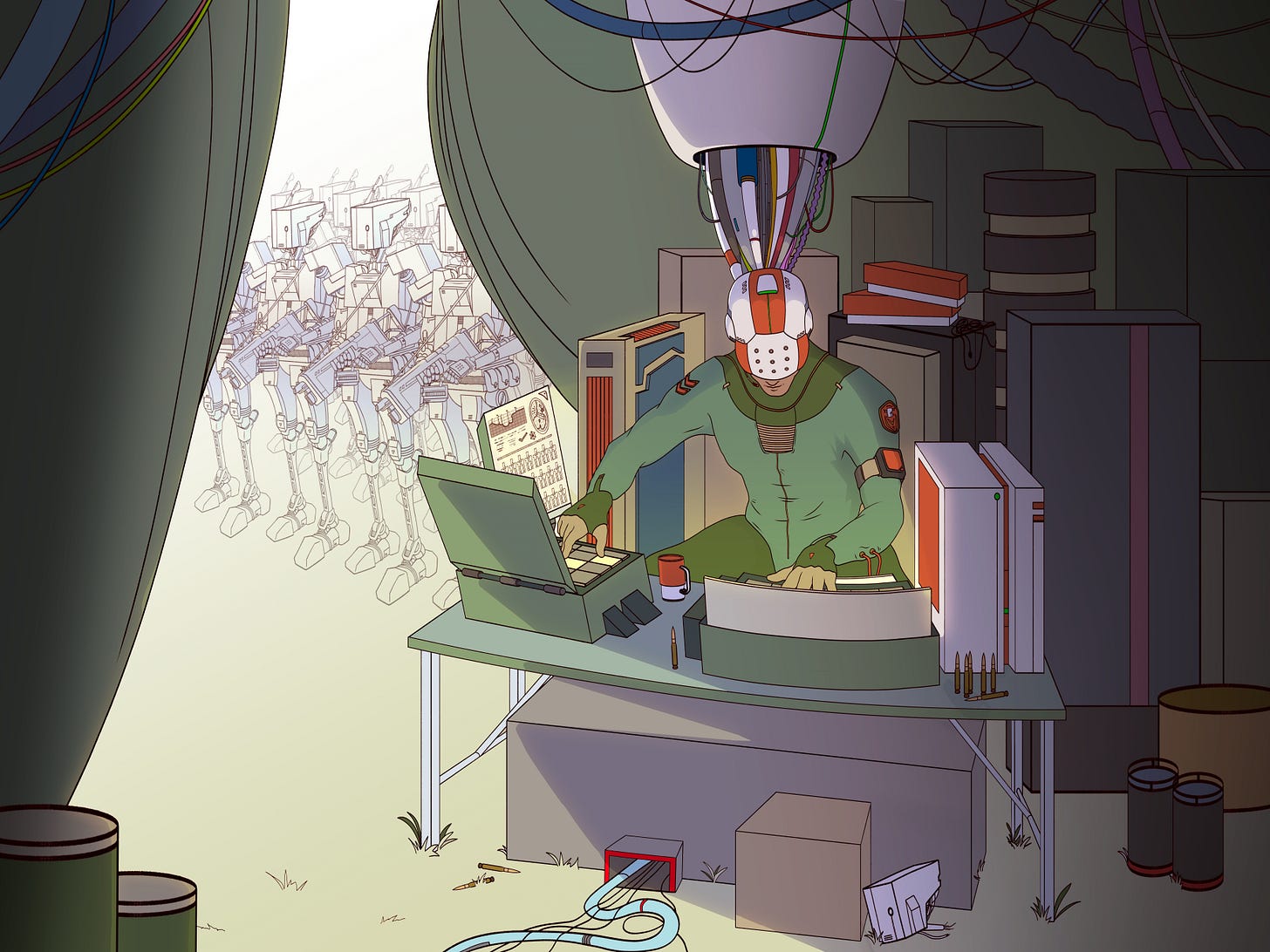

“Legions” by Andres Osorio

The world sat on the collective edge of its chair. On either side of a battlefield nearly fifty-eight miles square, the forces of the Russian Federation faced off against those of NATO-backed Ukraine.

The previous Russo-Ukraine war had ended in 2024, leaving deep scars in the Ukrainian psyche and continued territorial insecurity for Russia. In the intervening years, Putin — still alive, allegedly, now at the incomprehensible age of 103 — had made do with incursions into Georgia, Belarus, and North Korea.

But Russian preemptive defense was still top of mind, and without a more dramatic change in international affairs, a return to Ukraine was all but inevitable.

How exactly Putin had clung to power was a matter of substantial speculation. Many people believed that Cryo-Putin, reverse-aged with deepfakes to a healthy 68 years old in the media, had died years before. Yet the foreign policy of Russia seemed to indicate otherwise.

Now, arrayed across the field of battle, were two truly modern armies. Russia and NATO had fully absorbed the visions of war born in the 2020s, when AI first came to deserve its name. Russia, and Ukraine as NATO’s proxy, had invested in AI military intelligence and drone swarms, robots soldiers and automated cyberhackers.

It was promising to be a clash on an unparalleled scale, at least in the new modern age of robo-war.

* * *

War had changed dramatically in the past few decades. Scholars would trace the roots of the change to the world wars and the excessive human cost of conflict. In the popular imagination, however, modern war was born on the battlefield in Liechtenstein.

Liechtenstein was an unlikely place for innovation, least of all in military conflict. As a microstate with special tax arrangements for European retirees and less than forty-thousand residents, few would have anticipated the events of late 2031.

A few years earlier, the Sovereign Military Hospitalier Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and Malta had seen fit to create an arrangement with the House of Liechtenstein which would provide them with living space of their own.

The Knights of Malta, as they were often known, was a sovereign order. Not a nation per se, but sovereign nonetheless, acknowledged by the UN, and capable of issuing its own passports, coinage, and titles. Its thirteen thousand members were fiercely independent, and its loss of a home to Napoleon in 1798 was a persistent sore spot.

It was thus seen to be a tremendous boon when some micronation enthusiasts brokered a series of conversations with the House of Liechtenstein. The Prince and Regent of Liechtenstein was an ambitious man, and in conversation with the Prince and Grand Master of the Knights of Malta, both saw an opportunity to expand their sovereignty.

The deal was simple. The Knights of Malta would arrange a grant and the House of Liechtenstein would give the Knights control over a small piece of territory. Money for land. Liechtenstein would look — and actually be — progressive, pushing the envelope on the topic of sovereignty, while the Knights of Malta would have a home again.

The agreement was executed by a simple handshake, Liechtenstein and the Knights each relying on the others’ sense of honor to uphold the spirit of the deal. It made little news at the time, outside breathless coverage by the few publications devoted to charter cities and microstates.

Yet all was not well, as just a few years would reveal. The Knights wanted to “rule” their land; Liechtenstein wanted them merely to “control” it. Liechtenstein wanted to levy taxes; the Knights were willing to pay “fees” in the amounts agreed upon, but only if the payments were acknowledged as freely given.

To outsiders, these were trifling verbal disagreements. To the conflicting parties, they were core to the concept of sovereignty, which had been the point of the deal in the first place. Debates wore on, the Pope got involved, and the Knights hunkered down on land they had now grown quite attached to.

Neither party wanted the PR disaster of being seen bickering with another ancient order over a disagreement no one would understand. Yet public relations was secondary in an absolute sense to duty, and the labyrinthine requirements of each’s codes of honor interfaced strangely, computing a result no one could anticipate.

It was thus with great surprise that after more than three years of bitter interchange, the Prince and Regent of Liechtenstein and the Prince and Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Hospitalier Order, etc., of Malta publicly declared that they would resolve the dispute through a trial by combat.

The world was even more surprised when NVIDIA and Raytheon announced themselves as sponsors, and the combatants announced their plan to stream the entire battle live.

The Prince of Liechtenstein’s PR team had planned carefully. It was essential to avoid the appearance of antiquity; thus the trial would be conducted using the most advanced military technology available. It was also important to avoid critique; thus it would have to be the leaders who fought, not seconds.

The fact that the Prince was in his sixties and the Grand Master in his seventies only simplified matters. Each would command a robot army. Each would stand fully armored, in protective mech suits. Victory required capturing — not killing — the other. Technology, valor, and humanity, broadcast live to the entire world.

Behind the spectacle and glamor, however, were the reality of the stakes. The Prince and Grand Master had publicly committed, in front of the world, to conditions that would shape the future of their polities. With the world watching and the necessity of honor inviolate, the outcome of the battle would be binding.

Neither Liechtenstein nor the Knights of Malta had much budget for armed conflict. Liechtenstein had abolished its military in 1866; the Knights’ own modest military corps had served as a medical or paramedical unit in the Italian army since 1909. Sponsors took care of the shortfall, with Boeing, Anduril, Tesla, and Boston Dynamics joining the fray.

The result was a battle and media event that did not disappoint. The Grand Master’s army of modified bomb disposal robots and self-driving anti-aircraft batteries met the Prince’s drone battalion and leaping robotic landmines in front of 4.5 billion viewers, the third largest global audience for a single event up to that point. The Grand Master was captured, the Knights defeated, and the only person injured was the Prince, who slipped out of his mech suit when disembarking.

It was another four years until this trial by battle, robot version of capture-the-flag was tried again on the world stage. This time it was in Spain, with a new generation of Basque separatists demanding independence.

The idea was first floated on Joe Rogan Redux, where the host remarked to a guest that if the separatists were really serious, they should challenge the Spanish government to a duel Liechtenstein-style. Several separatist groups, brimming with youth and bravado, responded to the podcast saying of course they would fight, if only the government had the pelotas for it.

To their surprise, the Spanish government did have the pelotas. Or at least, its incentives were unusually aligned. The military wanted to test their technology and retain battle-readiness without having to fight a costly war. Policy wonks thought negotiation and limited conflict could bring extremists to the table and provide an outlet for “youthful energy.” The Spanish prime minister was the deciding factor, and he was up for re-election.

Negotiations proved difficult, with every point debated: size of battlefield, victory conditions, and most importantly, what would happen if each side won or lost. The negotiation seesawed back and forth between cooperation and brinksmanship, both sides making concessions, until finally the terms of battle were decided.

The Spanish government and the Basque separatists retained many aspects of the original Liechtenstein v. Knights encounter, including limitations on conflict and humane victory conditions. Modifications were made to account for the circumstance, permitting multiple combatants, lethal force outside of designated safe zones, and champions fighting in place of heads of state.

The conditions of conflict were announced publicly and the technology companies and arms dealers of the world raced to equip both sides. Fifty members of the Spanish army would face off against fifty separatists, each controlling one of two formidable robot armies, spread over a space of nearly two square miles.

The battle itself was mildly disappointing. The separatists’ electronic AI hacker army and drone swarm kamikazes disabled or destroyed half of the governments’ clunky steamroller robots, but only half. The government closed in on the separatist generals and the fight was over.

Unlike in Liechtenstein, this battle saw casualties. Three soldiers from the Spanish government side were killed after straying outside of the safe zone, and two separatists were killed inside the safe zone when their equipment malfunctioned.

The event did drive traffic, though, with 1.7 billion viewers, just shy of the 2030 FIFA World Cup and landing squarely in the top 20. It also yielded results: the separatists were demoralized, and most of their energy now poured into planning a rematch rather than following the path to real violence.

Other copycat events took place over the intervening years, but it would not be until 2046, eleven years later, that the true potential of limited robo-war began to emerge. Tensions between Israel and Iran had finally boiled over, and satellite imagery showed both countries preparing for a full-scale conflict.

The buildup on both sides was especially worrying because Iran now had nuclear weapons, at least according to the best-informed voices. Israel, of course, had had them for almost a century.

It was thus a matter of worldwide relief when Israel proposed that rather than all-out conflict, both countries demarcate a battleground — Syria was willing to host — and settle their differences the new-fashioned way. Which meant: cyber robot AI wartime.

Gone were the safe zones; anything in the battlefield was considered fair game. Gone were corporate sponsorships and comparisons to the World Cup — this was a deadly serious matter. Preparations on both sides were intense, Unit 8200 for Jerusalem and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Cyber Security Command for Tehran.

The political and military balance was complex. The purpose of war is, to some extent, to reduce uncertainty around who would prevail in an actual conflict. In theory, a limited, representative war could accomplish just that, at substantially lower cost.

Yet an intentionally limited engagement could always spill over into a full-scale war. It was thus to each side’s advantage to arrange a cyber duel that occupied just the right percentage of each side’s resources. Too low and it might not be representative. Too high and a crushing loss might leave the losing side undefended.

There was also the possibility of subterfuge, just like in any conflict. A country could conceivably play weak in robo-war to entice an enemy to mistakenly extend beyond the limited battleground. Or a country could put everything into the smaller war, hoping to disguise the weakness this would leave at home.

Each side thus had to consider whether the other side was treating the smaller battle as a distraction, or prelude, or the actual encounter, and whether each would believe the other’s assurances, or would make false assurances hoping to be disbelieved.

Indeed, the entire apparatus of statecraft was in operation from the beginning, Israel and Iran seeking to exploit every aspect of the process to weaken the enemy and seek advantage. Negotiations to distract and confuse, genuine attempts to extract concessions, and electronic sabotage meant to degrade each other’s systems before the battle even began.

It was understood on all sides that the zone of conflict would be bathed in signals from other countries, the US, China, and Russia expected to play a role, even while everyone denied it. Robots would be hardened against interference, and in many cases operate autonomously. Internet and cell phones would not operate; jamming would be ubiquitous. Drones and robots, flyers and diggers, systems reinforced with concrete and steel, resistant to heat and depleted uranium.

At the same time, the world watching, cheering for one side or another, for the two hundred men and women who would command the robot army for Israel and the two hundred men who would fly drones and pilot machines for Iran. Joining the human fighters would be thousands of robots and countless AI programs, viruses, and intelligent malware.

Limited cyberwar, as carried out now in more and more contexts, also offered a way out for those who did not actually want to fight a full war. Iran in this case, despite its rumored nuclear arsenal, was still importantly outgunned. It thus was possible — though may never be known for sure — that Iran accepted Israel’s proposal in order to save face and absorb a less costly defeat.

The four hundred combatants occupied positions on either side of a sparsely populated region in Syria. Nineteen square miles had been chosen for the battleground, civilians relocated, abandoned houses dotting the landscape. Makeshift fences with electronic sensors ringed the zone, with a buffer outside of nearly half a mile. Israel and Iran were granted safe transport to and from the battlefield, and worldwide peace organizations cut Syria a fat check.

The battles in Spain and Liechtenstein had lasted a few hours each. Israel v. Iran was expected to last weeks. Munitions and provisions were stored in fortified bunkers; restocking from the outside was not allowed. Real-time satellite images were broadcast live to the internet and media outlets were gearing up for twenty-four hour coverage and total market saturation.

As agreed, each side had been given exactly one hundred hours to enter its side of the battlefield, dig its fortifications, and prepare its offense and defense. The hours and minutes ticked away, and the world held its breath for the beginning of limited release armageddon.

The battle began with a simultaneous missile volley from both sides, filling the air with smoke and fire. One by one, reliable information sources were knocked out. Satellites couldn’t see, electronic sensors on the perimeter went dark. Eventually there was so much noise and static the only reports from the battlefield were coming from the Israeli and Iranian Ministries of War.

Israel and Iran, each with their own audience, pressed the media front mightily. Israel showed internal electronic footage and scans depicting their military robots crushing Iranian drone ships and micro-tanks underfoot. Iran cried foul and deepfake, and countered with its own depictions of Iranian valor, even despite overwhelming odds.

The outcome of the fight was the main question of popular interest. Military observers, however, were more concerned with whether either Israel or Iran would choose to go nuclear. Theorists proposed that in the face of defeat, either side might choose to destroy the entire battlefield, a sort of Simultaneous Assured Destruction. Triggering a SAD was considered poor sportsmanship, and environmentally damaging as well, but each might go ahead anyway and try to blame it on the other.

Days wore on, and as the smoke cleared it was apparent that Israel was winning. The victory conditions however were complex, and of the twenty-eight outcomes covered in the negotiation, Iran’s action still could decide between four of them.

Casualties were uncertain. Israel reported that forty-seven of its soldiers were down and twenty-nine unaccounted for. Iran did not give estimates. The number of soldiers left was unclearly related to battle outcomes, though, as between 20% and 60% of each side’s forces were fully automated, and as soldiers fell the robots would often fight on.

Finally, seven days in, the battle was over. US-Israeli computer worms had cracked the encryption on a set of Iranian control systems — somehow, despite the systems being airgapped. The Iranian defenses, already degraded substantially, collapsed completely and its remaining soldiers stood down.

Fans of Israel celebrated, glasses were raised and heroic moments recounted. The real test, however, was whether Iran would accept its defeat, and Israel its limited victory.

Weeks passed, and then, twenty-two days later, the prime minister of Israel and the president of Iran declared a full cessation of hostilities. Satellite imagery confirmed the demobilization and people in American and European capitals poured into the city streets.

While defeated, Iran had done better than expected, and the outcome now called on both countries to make changes. Costly changes, yes, though less costly than war.

* * *

The minutes counted down, and the second Russo-Ukraine war commenced.

Russia had opted for a larger battlefield. In return, Ukraine had pushed for smaller numbers of human combatants, in hope that its very best could command an automated army better than Russia’s.

It was thought Russia would focus on ground forces, as it largely had over the past several decades, aiming if necessary to outlast its enemy, rather than strike and win outright. Ukraine had thus prepared accordingly, with armor piercers and nimble low-flying explosive droneships.

Russia, though, had learned its lesson from its previous few wars, and pivoted hard on military strategy as the new front of limited robo-war opened up. With decentralized swarms and ‘bots that operated like fortified battering rams, with laser beams projecting an enormous Cryo-Putin head onto the smoke in the battlefield, this was a Russia no one had ever seen before.

The push for more space had thus been a ruse. Russian forces burst from their camp and made a blitzkrieg run for the Ukrainian base. Ukrainian operators, scratching their heads at what their electronic sensors told them, expected the Russian forces to reach the midway point and then stop. But they just kept coming.

Recovering too late, Ukraine rushed to reprogram its drones and consolidate defenses. But the Russian missile bots and close-range targeting algorithms, complete with laser-projected psyops, could not be stopped, to the shock and dismay of viewers worldwide.

Analysts would later note that the Russian victory indicated Russia’s amenability to limited conflict and that economically, it made sense for Russia to embrace this new and cheaper form of war.

In the meantime, there was the embarrassing and difficult fact that Russia had won rather decisively. Yes, some of its robots had gone haywire and done tens of millions of dollars of damage outside the demarcated zone. But that did not seem sufficient reason to annul or resist the result, which was that Ukraine was now supposed to hand over to Russia territorial control of one of its provinces.

Viewers everywhere knew what was supposed to happen next. The alternative was an escalation of unknown magnitude. Russia was ready to accept its victory, restoring more of its original USSR territory and giving it a larger buffer against NATO.

What did a Russian victory portend? Commentators conjured visions of a new Napoleon, a new Caesar or Alexander, seeking to conquer the world one robo-battle at a time. Precedent was being set, and the more deeply it became entrenched, the more a deviation would signal cause for real war.

Real war. Of the two-hundred and eighty two soldiers in Russia v. Ukraine, ninety-seven of them had died. Yet now the political fate of almost two million people was to be determined, certainly for the worse. With no real plans to the contrary, Western words of defiance fell flat, and the machinery of government and bureaucracy set in motion to effect a peaceful transition of power.

It was unexpected and tragic. Though for all that, the Western world slept easier, even in defeat. There would be future opportunities for victory and glory, as the great game of geopolitics assumed its new form.

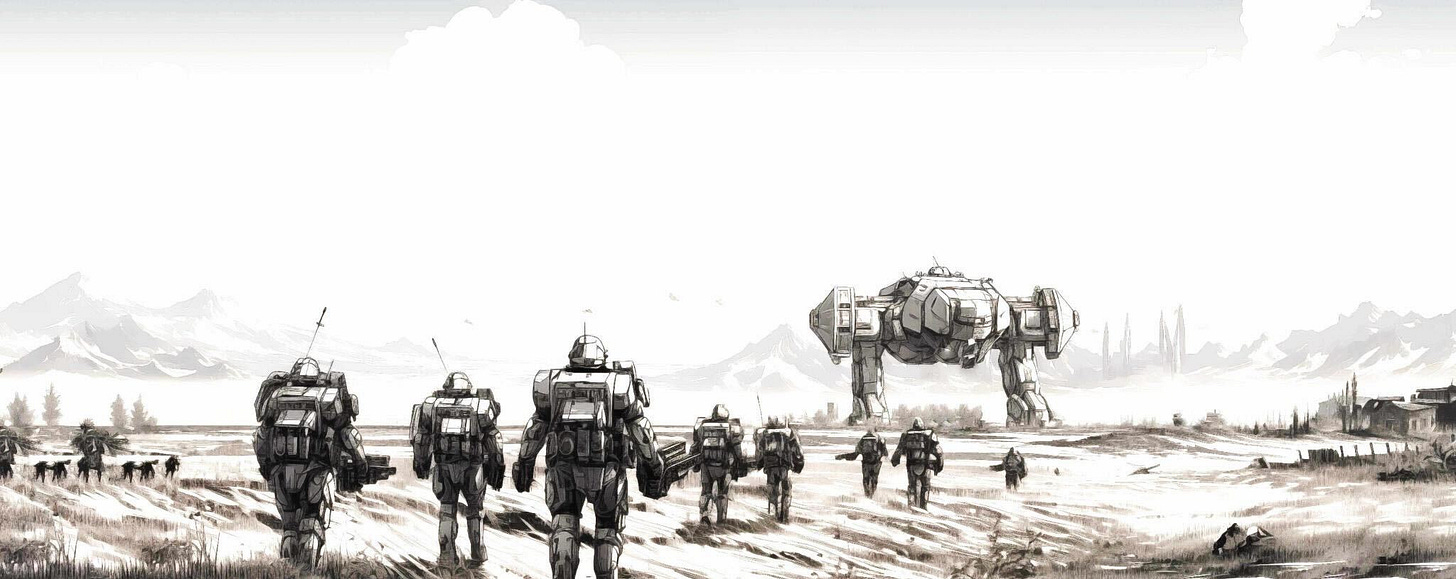

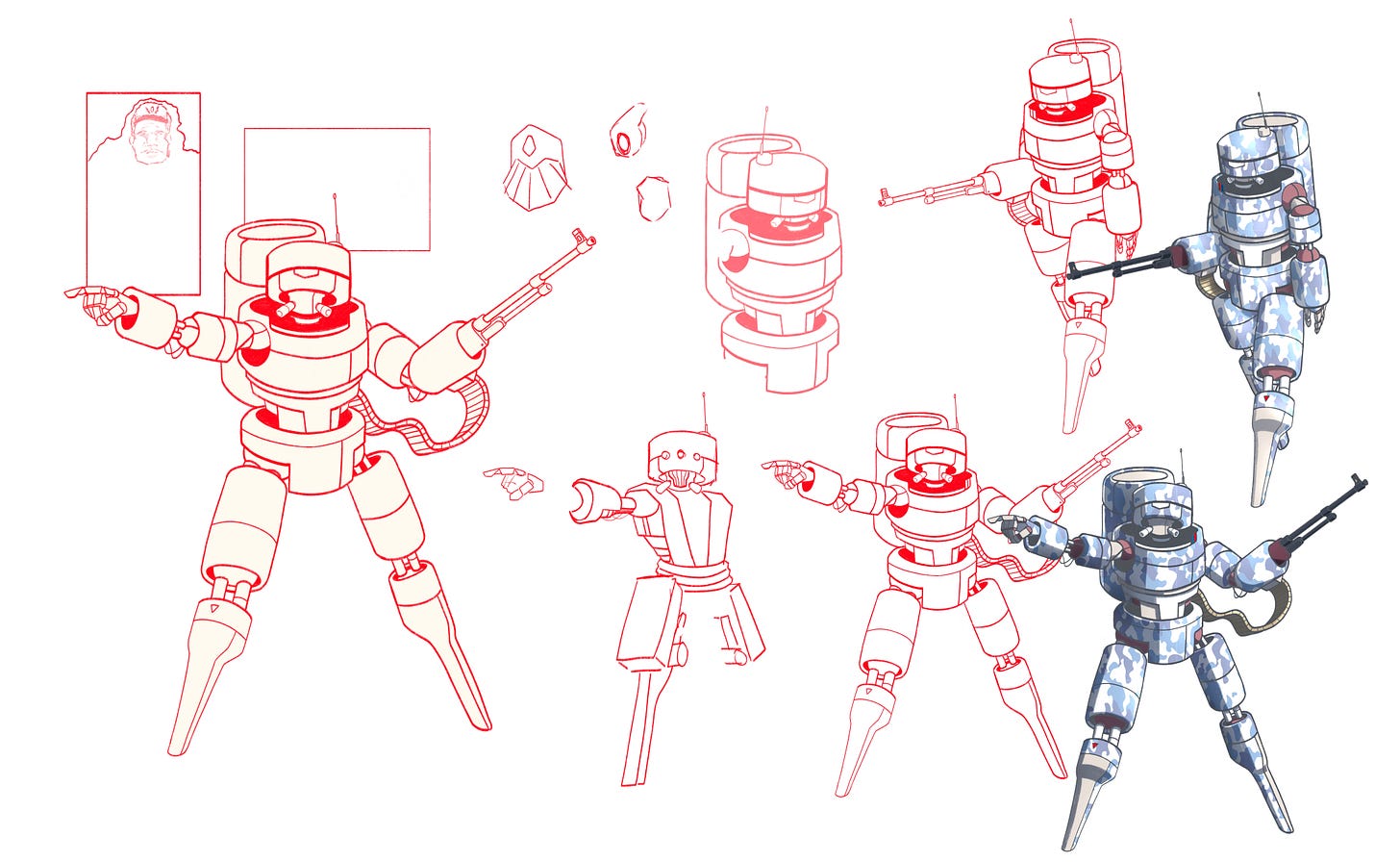

Story Art

by Andres Osorio

“The Prince of Liechtenstein”

“Proxy War Technician”

“Cyper Putin”

Limited Warfare

a companion piece by Ben Landau-Taylor

In addition to the physical, mechanical, and electronic, war also involves social technologies. Some, like the use of champions and trial by combat, are the province of myth or have played a relatively small role historically. The idea of limited conflict, however, is a social form or technology with a serious history.

When fighting wars, societies can deploy more or less of their resources, armies can target or spare civilians and infrastructure, and leaders can pursue permanent conquest of the enemy or limited concessions from the opposing government. Escalation in one area usually comes with escalation in all areas; the opposite is true as well.

Modern readers will be most familiar with the opposite of limited conflict, namely, total war. Our template for this is the Second World War, which saw historically unprecedented mobilization, industrial-scale atrocities against civilians by all sides, and beleaguered armies fighting on until they lost all ability to resist. It ended with the unconditional surrender of the Axis nations, which had their political systems completely remade in the image of their conquerors and remain militarily occupied to this day.

By contrast, the European wars of the 18th century were very limited. The Seven Years’ War of 1756-1763 is representative. While there was large-scale mobilization, soldiers generally did not target civilians. They mostly obeyed the laws of war, and armies would often surrender if a lost battle or two put them in a poor situation. At the end of the war, most of the conquered territories were returned to their previous rulers, with the major powers ceding to each other only some overseas colonies.

Limited war for limited aims is a fairly stable equilibrium. Achieving it depends on the prevailing culture, political stakes, and decisions of key individuals. If we want militaries to limit the means of war, statesmen and diplomats must limit the aims of war. When a government is losing, if it has good reason to believe its adversaries will accept limited concessions, it will usually abide by the result. If an adversary insists on deposing their foe’s government, whether in service of conquest or ideological goals, the underdog will almost always escalate rather than concede.

Culture and technology both determine, to a degree, the feasibility of limited conflict. The culture of the Enlightenment, with its focus on ideals and ideology, helped contribute to the rise of the mass idealistic army, first constructed by Napoleon. Such armies are difficult to deploy for limited aims, and their use by Napoleon and later in the World Wars led respect for the laws of war to break down and tens of millions of deaths.

Nuclear weapons led to the return of limited war, under the threat of mutually assured destruction. The Cold War thus saw the U.S.A. and U.S.S.R. build nuclear arsenals and contemplate using them against enemy cities en masse, though in practice limit their globe-spanning conflict to numerous smaller proxy wars.

War need not be fought to the bitter end. Culture has changed and new technologies, especially the internet, have made worldwide communication and commentary about war possible. While belligerents even of limited wars are unlikely to restrict themselves to sportsmanlike rules such as designated battlefields or limits on their forces, future wars could nevertheless be decided with relatively little loss of human life, if someday in the future the best weapons systems should be mostly autonomous. Whether people will recognize the feasibility and benefits of limited war, and the changes to our expectations that will require, is something time will tell.

A Conversation with Christian Wolff

Our editors Charles Rosenbauer and Olli Payne find out Christian’s motivation for writing Cyber Robot AI Wartime and his thoughts on why limited warfare is a good path for humanity.

0:00 - Inspiration behind the story and the title

3:11 - The Realistic

8:46 - The Optimistic

13:39 - The locations & how we adopt limited warfare

20:25 - The medium of Sci-Fi

25:33 - Public perception of the story

33:54 - Christian’s writing process; Humans and technology

44:25 - What we’d like to see in upcoming stories

54:58 - Christian’s favorite sci-fi & unconventional technologies

Concept Work

by Andres Osorio

“Taking the Field”

“Cyber Robot AI”

Thank you for reading Possibilia Magazine 🚀

Compelling story telling that also brings up an interesting question.

Who would win in a world war type of situation?

Who would fight, who would stay out of it?

Would japan bring in giant mecha?

Annie Jacobsen's new book NUCLEAR WAR: A SCENARIO is partly about how autonomous systems make escalation more likely, in part because they are designed to react as fast as possible.

"The scenario is based on known facts concerning the world’s nuclear arsenals, systems and doctrine. Those facts are all in the public domain, but Jacobsen believes society has tuned them out, despite (or perhaps because of) how shocking they are."

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/31/annie-jacobsen-nuclear-war-scenario