The Long Way Home: Brushcross, TX

A Barn Futurism Artifact

Aug 15th, 2064

After Lesath, I decided to take up the friendly offer of Clark, a man who I met while perusing the Recent-History Museum at The Boulton. He invited me to visit TerraMar, his amphibious vehicle startup in Brushcross, Texas.

I arrived yesterday afternoon in the city of Parvis by electric rail and was relieved to see that the station runs a small fleet of self-driving EVs for getting out-of-towners to their destinations. They were kind enough to let me charge my folding electric bike at one of their stations in case I needed it while I was in town. While I waited, I took a stroll around the block, passing by a memory cafe and opting for a refreshing lavender and honey tea from a nitro boba stand on the edge of a public plaza. It was a nice day out, and I enjoyed the shade in this alcove where people came to sit and read or enjoy a picnic.

My journey to a small ranch owned and operated by TerraMar would be a bit of a trek. The first leg would be 25 minutes by EV to the shipping district, followed by another hour in a passenger car on a freight train that makes a routine stop right at their barn. I could more reasonably take the EV all the way in, but I decided to follow Clark’s recommendation that I experience the line.

As the car hummed its way into more sparsely-populated lands, I noticed the shift in architectural styles from the newer trends of Neoclassical Futurism to the retro 2020s style Modern Farmhouse, with much older structures dotted throughout at various stages of refurbishment. Not long after getting settled on the train I noticed something else too - barns. More and more became lots and lots, and by the time I arrived at the TerraMar ranch it was the case that few if any ranch or residence I passed was lacking one.

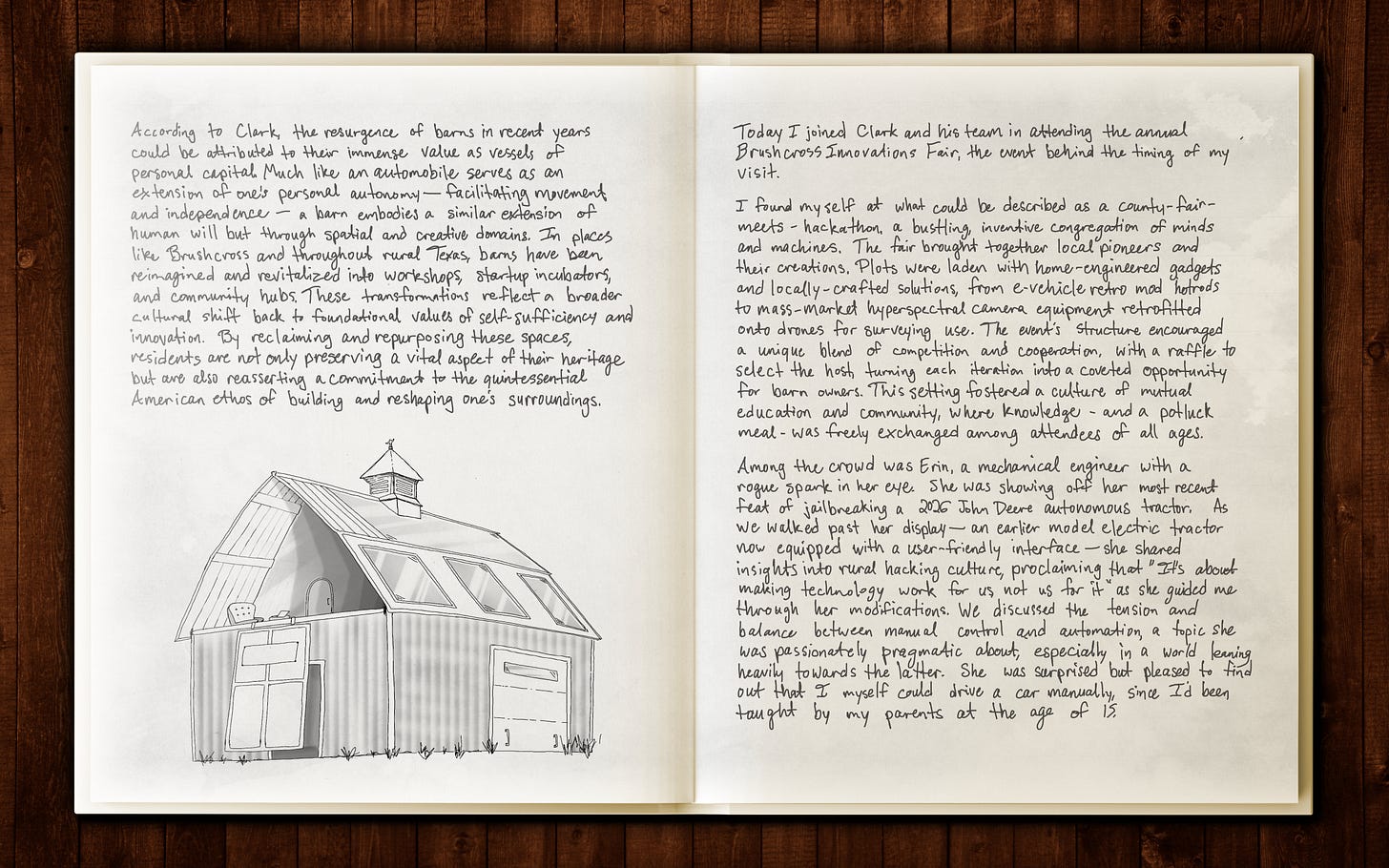

The ranch was no exception, and offered me insight into the culture of the pastoral yet lively sprawl. The structure that their team works out of was built on the bones of a towering 19th century barn. The foundational frame was a 1-to-1 replacement of its original solid wood beams, and the interior featured a refurbished loft space for coworking above their logistics workspace. The roof above the loft invited light in through large windows of insulated glass. Stalls that had undoubtedly been occupied by animals in its past life now served as storage areas with garage doors for ease of access when it came time to ship. The exterior was made of corrugated metal but was painted red and white in tribute to the iconic image of a classic barn, despite there being no external wood to save from weathering.

According to Clark, the resurgence of barns in recent years could be attributed to their immense value as vessels of personal capital. Much like an automobile serves as an extension of one's personal autonomy—facilitating movement and independence—a barn embodies a similar extension of human will but through spatial and creative domains. In places like Brushcross and throughout rural Texas, barns have been reimagined and revitalized into workshops, startup incubators, and community hubs. These transformations reflect a broader cultural shift back to foundational values of self-sufficiency and innovation. By reclaiming and repurposing these spaces, residents are not only preserving a vital aspect of their heritage but are also reasserting a commitment to the quintessential American ethos of building and reshaping one’s surroundings.

✷

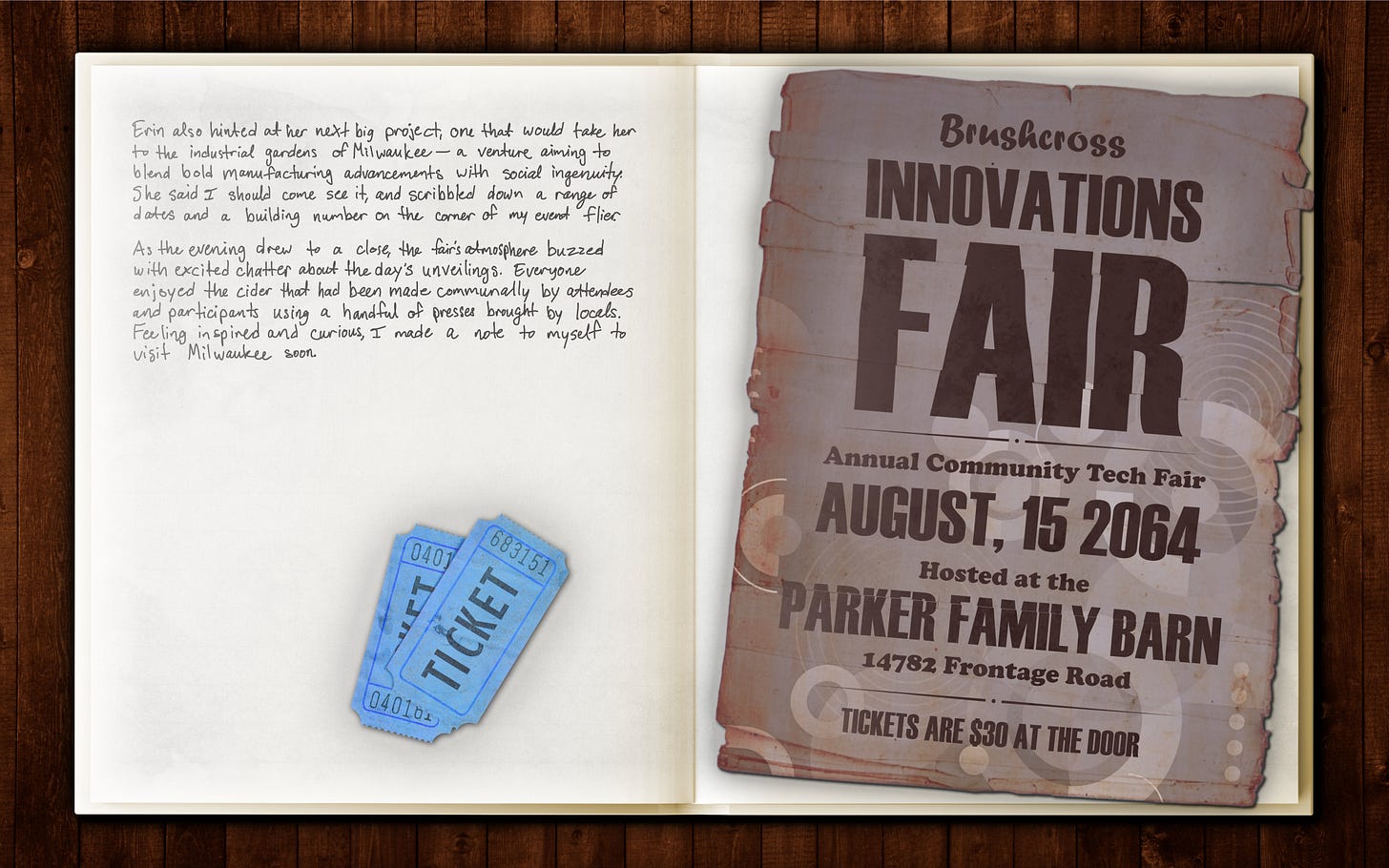

Today I joined Clark and his team in attending the annual Brushcross Innovations Fair, the event behind the timing of my visit.

I found myself at what could be described as a county-fair-meets-hackathon, a bustling, inventive congregation of minds and machines. The fair brought together local pioneers and their creations. Plots were laden with home-engineered gadgets and locally-crafted solutions, from e-vehicle retro mod hotrods to mass-market hyperspectral camera equipment retrofitted onto drones for surveying use.The event’s structure encouraged a unique blend of competition and cooperation, with a raffle to select the host, turning each iteration into a coveted opportunity for barn owners. This setting fostered a culture of mutual education and community, where knowledge - and a potluck meal - was freely exchanged among attendees of all ages.

Among the crowd was Erin, a mechanical engineer with a rogue spark in her eyes. She was showing off her most recent feat of jailbreaking a 2026 John Deere autonomous tractor. As we walked past her display—an earlier model electric tractor now equipped with a user-friendly interface—she shared insights into rural hacking culture, proclaiming that "It's about making technology work for us, not us for it," as she guided me through her modifications. We discussed the tension and balance between manual control and automation, a topic she was passionately pragmatic about, especially in a world leaning heavily towards the latter. She was surprised but pleased to find out that I myself could drive a car manually, since I’d been taught by my parents at the age of 15.

Erin also hinted at her next big project, one that would take her to the industrial gardens of Milwaukee—a venture aiming to blend bold manufacturing advancements with social ingenuity. She said I should come see it, and scribbled down a range of dates and a building number on the corner of my event flier.

As the evening drew to a close, the fair’s atmosphere buzzed with excited chatter about the day’s unveilings. Everyone enjoyed the cider that had been made communally by attendees and participants using a handful of presses brought by locals. Feeling inspired and curious, I made a note to myself to visit Milwaukee soon.

This vignette is part of a series, the previous entry can be read here:

We welcome you to become a paid subscriber for access to the internal notes behind The Long Way Home: Brushcross, TX.